St Benedict

1,478 years ago today, our holy Father St Benedict gave up his pure, humble soul to God. Since then, he has not ceased to gather together disciples around the world in monasteries of both monks and nuns, in every country, clime and language …. All the sons and daughters of St Benedict seek to live according to the Rule that he wrote for us, albeit with local adaptations and various ways of interpreting some aspects of the written Rule, and the sound traditions that we know he followed as did his successors. Every monastery, though attached to St Benedict, has its own history and its own pre-history. There are people and places and graces and teachings that go into making each monastery. That is why each monastery, like each person, is unique. Let’s evoke just one example we are quite familiar with: the restoration of monastic life in France after the Revolution. The two main catalysts of this restoration were Dom Prosper Gueranger, founder of Solesmes, and Dom Jean-Baptiste Muard, founder of La Pierre-Qui-Vire. Both were fully Benedictine, but both lived out the charism in very different ways. Solesmes focused on the solemnity of the liturgy and erudition; La Pierre-Qui-Vire focused on austerity and outreach through parish missions.

Our little community here has a unique history, descending from the Olivetan (or white) Benedictines through Flavigny, whose charism of monastic life and retreats is very similar to what Dom Muard had achieved in his day but also contains serious input from the sons of Dom Gueranger thanks to a close relationship with Solesmes. In some ways, we unite these two charisms. What makes us different from Olivetans, Solesmiens, and, shall we say, Muardists, but close to Flavigny and Solignac, is our attachment to the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius. This is by no means neither incidental nor accidental. It is essential. The Exercises help us live the Rule better and do better what we do because the Exercises provide us with our primary means of offering spiritual hospitality here and around the world. Let’s evoke, for today, two aspects of the Ignatian exercises that help the monks, first of all, to live the Rule more deeply. If we understand and live it, we can then share it with others.

The first concerns the discernment of spirits. In the prologue of the Rule, St Benedict tells us that the monk is one who “graspeth his (Satan’s) evil suggestions as they arise and dasheth them to pieces on the rock that is Christ”. It’s a magnificent expression with an implicit reference to Psalm 136. As it goes with such forms of speech, it englobes all forms of evil suggestions but does not expound on what they are at the concrete, practical level, though, of course, we know that they are any temptation to evil. St Ignatius, for his part, helps us to understand what is at stake in these suggestions when he tells us that the enemy does not use only obviously sinful thoughts (anger, envy, lust, etc.) but also more subtle ways of causing desolation, such as “darkness of soul, turmoil of spirit, inclination to what is low and earthly, restlessness rising from many disturbances and temptations which lead to want of faith, want of hope, want of love” (Sp. Ex 317). He even goes further and tells us that for those who are advancing in the ways of the Spirit, the enemy sometimes takes on the form of an “angel of light”, proposing some good thoughts that are wholly in conformity with the soul, in order to lead that soul to his own perverse ways (Sp. Ex. # 332). These indications concerning the intentions and tactics of the enemy are priceless. In the spiritual combat, many are waylaid for not knowing or failing to consider them. How many times have souls – even religious and monastic souls – been led to spiritual disaster because they had a good inspiration while at prayer, took it at face value as being from God, but failed to discern it and submit it to their spiritual guide who has the grace of state for this kind of discernment. The enemy is quite happy to take one step forward as long as he has the hope of making you take two steps backward in 3 months or 3 years’ time.

One of the reasons many fail in this discernment is that this spiritual combat takes willpower and energy. When one is under the Satanic spell of desolation, it’s so easy to go and throw a pity party to which we are the only invitee but to which the devil, you can be sure, invites himself. On the other hand, when one is taken and even blinded by some brilliant thought, it is so hard to row against the current and seek advice from a solid, experienced spiritual guide, especially if we suspect he might point out a flaw in our mental construction. St Benedict speaks of dashing the thought against Christ, but he does not give explicit information on how to do it. St Ignatius tells us: in time of desolation, be faithful to your resolutions and don’t change. In times of consolation, be circumspect and careful. Not all that glitters is gold. In both cases, open yourself up to your superior. He has the grace to guide you. The man who obeys himself obeys a fool.

A second way in which St Ignatius helps us live the Rule better is in his teaching on humility. Everyone knows that humility is the Benedictine virtue par excellence. When we read the fourth degree in chapter 7, we can be somewhat terrified. In that passage, our patriarch says that when the monk meets with injustice (social warriors, be attentive!), he should quiet his thoughts, be patient, endure, and not run away. In all adversities and injuries, he should turn the other cheek and remember that the Lord set men over us precisely in order to humiliate us because only humility saves (Rule, ch. 7).

Let’s be honest and admit that when we modern emancipated revolutionaries read this text, we can feel something like terror and even revolt. What medieval nonsense is this! And yet, the monk makes a profession to follow the Rule, and the Rule captures the essence of the Gospel. While Benedict insists that the monk be humbly submissive, quoting several psalms and St Paul, Ignatius, for his part, gives us some very concrete advice on how to make this happen. It is my personal conviction that Ignatius understood the fourth degree of humility better than anyone. Let’s not forget that during the three years he spent in solitude writing the Spiritual Exercises, he was under the direction of a Benedictine monk at Montserrat. I suspect that this born warrior struggled with Benedict’s teaching. He knew it was the very substance of the Gospel, but as a good solider, he wanted a practical way of living it out. The solution he came up with and offers us in the Exercises comprises two essential parts. The first is the lengthy, even lifelong, contemplation of the life and passion of Our Lord. It is in admiring humility in Our Lord that we want to be humble like Him. So it is that we ask for the grace to know Him intimately, to love Him ardently and to follow Him more closely. We ask to share in His sorrow and bear His cross.

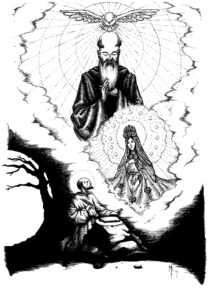

But there is more. Bringing his teaching to a summit that I contend is unsurpassed in the annals of spirituality, Ignatius goes straight to the root of the problem, which is our stubborn will. If we are to embrace the humiliations of Christ, we must want to be like Christ humiliated, and for that, quite simply, we must ask, we must beg, we must plead with Him for this grace, this grace to share His poverty and humiliations. It is the celebrated Triple Colloquy that concludes the Meditation on the Two Standards. The soul that makes that colloquy frequently and fervently will inevitably want to be humiliated like Our Lord, and so when the humiliation comes, he is ready and accepts it with much profit for his soul. Saying this prayer is the best way to achieve the 4th degree of humility, and the one who has this fourth degree has all the others.

Those are just two of the ways in which our practice of the Exercises is destined to make us better monks. There are many, many more. But this is enough for today to help us understand why the Venerable Benedictine Abbot Louis Blosius, a contemporary of St Ignatius, when he heard of the Exercises, made them himself and had all his monks make them. He knew the Exercises would make them better monks. There is no cause for surprise here, nor is there anything not Benedictine about it. There are many other examples that could be brought forward, and many teachings, first of whom is St Benedict himself, who makes it clear that the Rule is just a beginning and that he intends for his monks to find more spiritual nourishment wherever it is to be found.

All this should help us appreciate the immense Gift that the Lord has made over to us, the treasure hidden in the unlikely field that is ours here in Colebrook. Let us ask St Benedict today for the grace to treasure the Gift and, in its presence, to never lose the awe and the wonder of the child on Christmas morning. If only we know how to exploit that treasure for ourselves and others, we will truly be sons of the great patriarch of monks who tells us at the end of the Rule that by observing it, we are making a good start, but that the true heights of perfection are elsewhere. “At length under God’s protection thou shalt attain to the loftier heights of wisdom and moral perfection” (Rule, Ch 73).