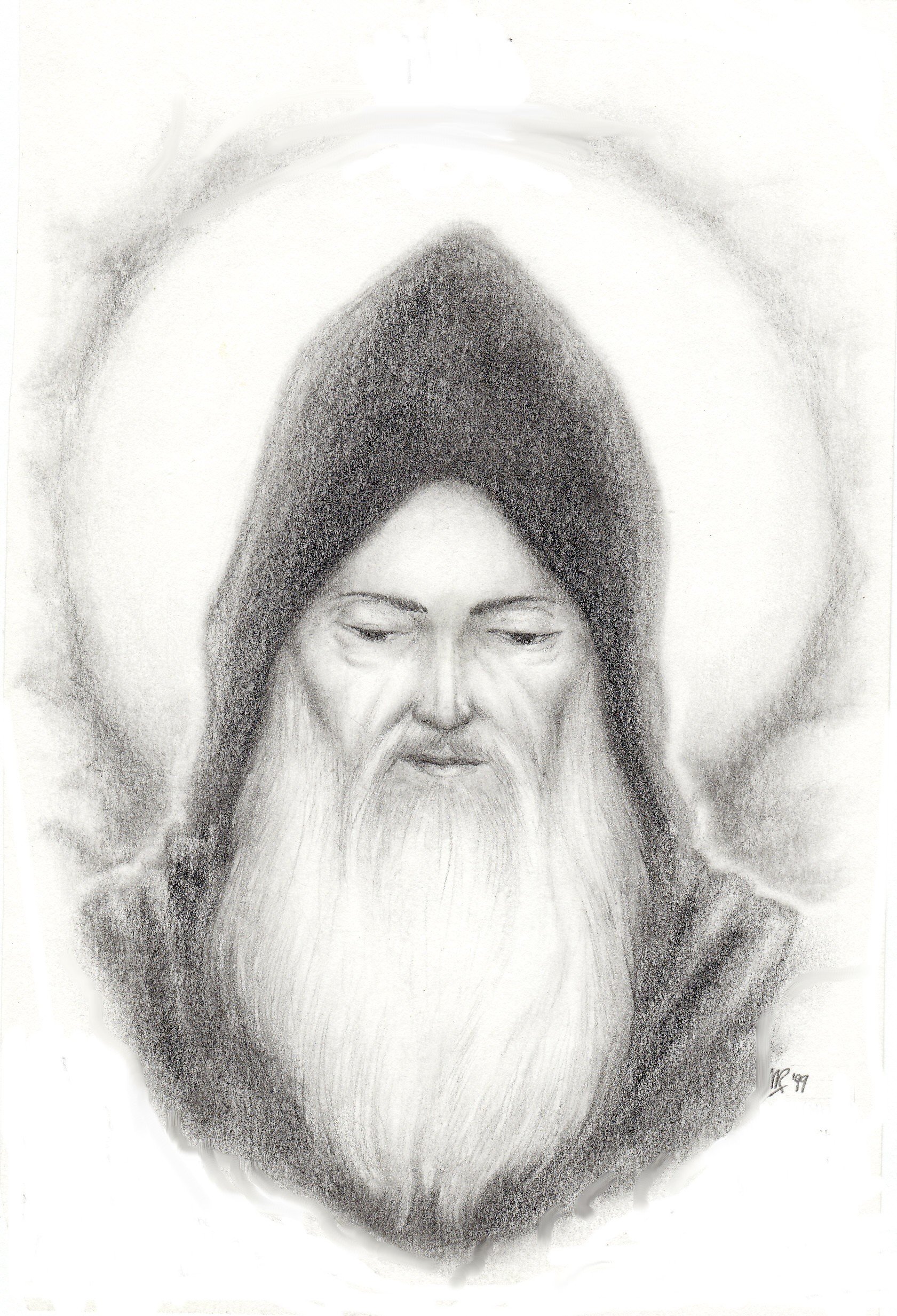

Solemnity of St Benedict

In his Subiaco address pronounced just a couple weeks before his election as Pope, Cardinal Ratzinger pointed to our holy father St Benedict as one of those men who kept the flame of faith alive in the dark ages and prepared the Church and Europe for the real spiritual renewal that would take place centuries later.

When Benedict breathed his last, the Roman Empire, that is to say the rule of law that everyone had known and counted on for centuries, was falling to pieces. The monks that St Benedict had founded and to whom he had bequeathed his Rule, would commence the reconstruction, but that reconstruction had to begin with the foundations. So down then went, delving ever deeper into the abyss of their own nothingness and God’s infiniteness. The deeper they went, the more they were purified, and at last, were able to rise up at the appointed time, and give the Church some of its most renowned and venerated pontiffs. What came to be known, after the elevation of Hildebrand to the throne of St Peter, as the Gregorian reform, owes its impetus to those generations of monks who, in the midst of the general disarray, had the faith and the courage to go out into the deserts, the forests, and up the mountains, to fight the true fight of the spiritual combat, and rise purified to lead the Church.

It does not require profound intelligence to note the similarities between St Benedict’s day and ours. The civilisation around us is collapsing, digging its own grave with lightning speed, totally unaware of the impending disaster because intoxicated with pride for its technological prowess. Since we are in a very similar situation, it would be good for us to reflect a bit today on what actually made Benedict’s monasteries places in which could be forged the likes of a Hildebrand. What was Benedict’s secret that continues to this day to draw men and women to seek to achieve his ideal? No doubt, we would all unhesitatingly think of his insistence on love for Christ, for humility, for obedience, for his genius in organising life in common, balancing the primordial role of the abbot with care to listen to the community. All that is very true. Today however I would like to dwell somewhat upon a recommendation that does not appear until the end of the Rule. It was providentially mentioned last night in the refectory in very similar words in the writings of St Elizabeth of the Trinity. St Benedict expresses it in chapter 72, which is something of an addendum to the instruments of good works, or perhaps the ones which, after so much experience, he had come to understand were the most important. He writes: Let none follow what seems good for himself, but rather what is good for another.

At first sight, this recommendation might go unnoticed, but at closer inspection, we find that the glorious patriarch here taps into what we must consider as the most important disposition for the religious soul. As St Elizabeth wrote so well, this is truly the litmus test for sanctity, for in the end, there are only two kinds of souls: the immense majority, who remain self-centred, and the tiny minority who succeed in leaving themselves behind. In both camps there are varying degrees. Sadly, most souls are self-centred to the point of virtually, though not actually, being idolaters. As St Paul says, their god is their own belly (cf. Phil. 3:19). When we pass over onto the side of those who seek to go out of themselves, we all know by experience that it is not the work of a day, or even of a few years, although giant saints, such as Elizabeth and Therese, mastered the art in a very short time. For most of us, it is a long struggle, this reformation of the old man in us, the renunciation of our sinful manners, our egotistic way of looking at others and the world. Sadly, as St John of the Cross says, many reach the night of the senses, but most turn back, lacking the courage and the generosity, and thus remain spiritual dwarves. We would not readily admit it, but does not the world really revolve around us? Are we not the object of our continual thoughts and actions? It is good to become conscious of this, for it is the first step towards getting out, turning to others and above all to the Other.

It is to this purpose that our holy Father organised the entire monastic life. Its very structure is destined to help the monk by calling him continually to the service of God and neighbour. This is why St Benedict is truly to be placed on a par with the great mystics who later formulated with great precision the steps towards the leaving behind of self and the entering into the divine cloud, which because of our imperfection, is perceived as dark. This is what Cardinal Ratzinger referred to when, in the Subiaco Address, he said: “Only through men who have been touched by God, can God come near to men. We need men like Benedict of Norcia, who at a time of dissipation and decadence, plunged into the most profound solitude, succeeding, after all the purifications he had to suffer, to ascend again to the light, to return and to found Montecassino, the city on the mountain that, with so many ruins, gathered together the forces from which a new world was formed. In this way Benedict, like Abraham, became the father of many nations.”

Like Abraham, he had to step out in faith, not knowing where he was going. He had to sacrifice his Isaac, as he did when he left his paternal home, and then later his beloved solitude too he had to leave behind. He had to go into the dark night in which there is no path. He knew that it is not possible to attain to the heights of sanctity if one approaches the religious life from a legalistic perspective. The monk is one who seeks to give himself, to renounce all self-interest, and that, of necessity, includes accepting situations that from a purely human perspective, are unfair, as is made crystal clear in the fourth degree of humility. The monk must be able to stand his ground, to endure, when treated unjustly, for it is then, and only then, that he enters into the path of real virtue, of true and lasting sanctity.

Almost 60 years ago Pope Paul VI consecrated the rebuilt abbey church of Montecassino. On that occasion he proclaimed St Benedict to be patron of Europe and wanted the ceremony of the rebuilt abbey to be the symbol of a rebuilt Europe after the destruction of the Second World War. Little did he realise that it would soon be the Church herself which would need rebuilding. Today our beloved Church is in ruins. The announced springtime became one of the darkest and coldest winters she has ever endured. And there is no end in sight. The children ask for bread and they receive stones. They ask for the clarity of truth and they are given more confusion. The situation has existed before. The early 16th century saw the Church in the hands of ambitious, lustful men who cared only about themselves. In that context, as in the 6th century, holy men knew that there was only one course of action: put out into the deep, go back to living the life of holiness that our fathers gave us. In mountain climbing, when you realise you are lost, you must go back. To not do so, is suicide.

St Benedict reminds us, age after age, that neither the faith nor the path to sanctity are to be reinvented. He beckons to us to get out of ourselves and our petty ambitions, to leave behind our self-conceit, to renounce the folly of thinking that we can remake the Church in our own image. He teaches us to accept to go through a purification, for a fire must be lit in the heart of every man who comes to the service of God, and fire burns and causes scorching pain. In doing so, it purifies and hardens, it galvanises the soul and makes it ready for the reconstruction that will come and for which men of God will be needed.

It is only by accepting to descend into the abyss of one’s nothingness that one can meet the abyss of God’s infinite grandeur, the ocean Elizabeth speaks of at the end of her prayer to the Trinity. Sometimes one must give up something so that others can have it. Such is the teaching of the Imitation of Christ: Totum in moriendo jacet – all consists in dying. And this in turn is quite simply the Gospel spelled out: He who loses his life will find it (Mat 10:39). Unless the grain of wheat dies, it remains alone, but if it dies, it bears much fruit (Jn 12:24).

Let us on this day, as devoted sons, offer to our holy Father St Benedict our gratitude for opening up for us this path. Let us thank him for the courage he showed when he left the paternal home and the prestigious career that awaited him, and took flight to the desert. Let us thank him for the merciful love with which he accepted to become abbot of the monks in Vicovaro, those same monks who would soon be his would-be assassins. Let us thank him for accepting to found Montecassino, the city on the mountain, from which his order would illuminate the world. Let us thank him for the strength of character he showed in destroying the altars of the idols and holding up high the torch of the true faith. Let us thank him for the lesson in fraternal charity he gave by not neglecting, under pretext of a contemplative life, the souls that came to him and needed instruction and evangelisation. He had indeed learned, in the dark night of his own soul, that a true monk cannot be oblivious to any needs that may arise, but rather, if his love for Christ be true, must manifest itself in love for souls, for, as St Augustine would say: there is only one love.

May our holy father give each of us to march resolutely in his footsteps, with the unshakeable conviction that right here and right now we can and must glorify God by our lives by following not what seems good for ourselves, but rather what is good for another.